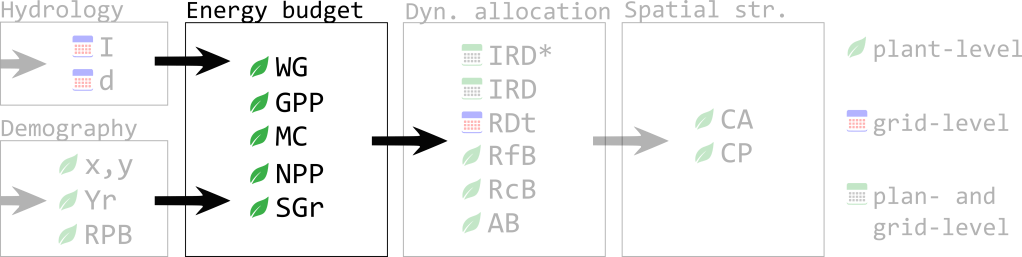

| Name | Description | units/level |

| GPP | Gross primary productivity | g.plant-1 |

| MC | Maintenance costs (to support current plant tissues) | g.plant-1 |

| NPP | Net primary productivity (=GPP-MC) (g/day) | g.(day.plant)-1 |

| RPB | Reproduction biomass | g.(day.plant)-1 |

| SGr | Net biomass available for somatic growth | g.(day.plant)-1 |

| WG | Water available for growth, ESPR-based | l.(day. plant.cell)-1 |

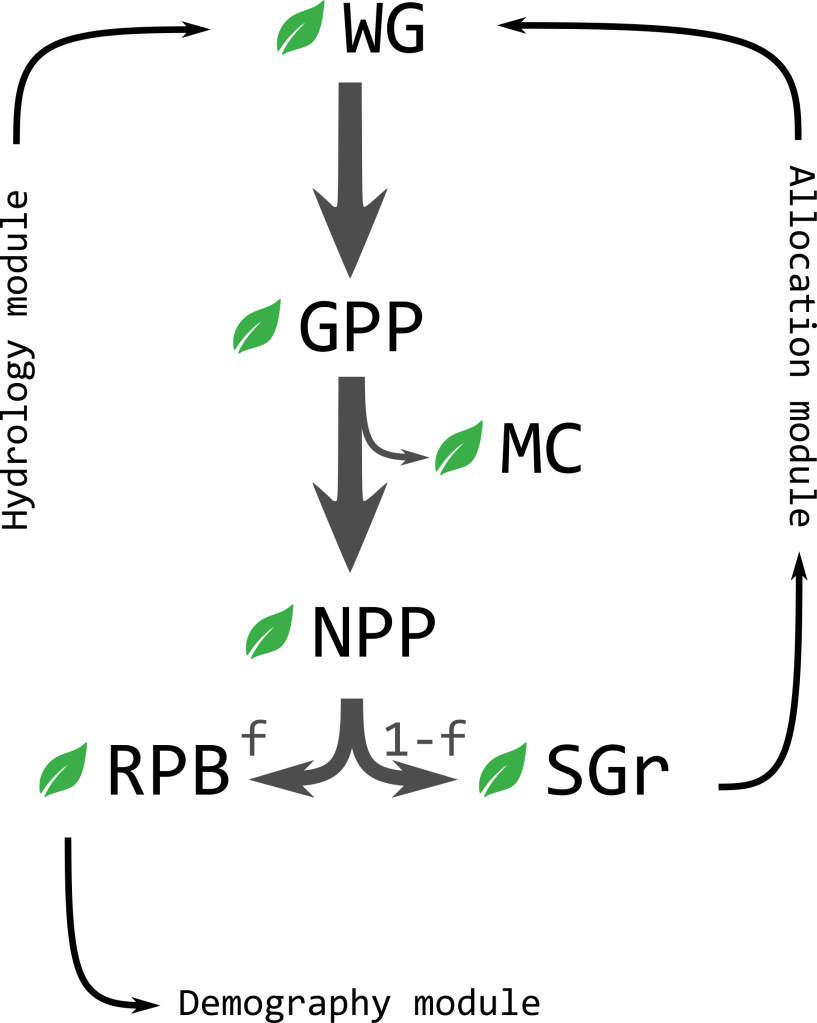

The dynamic allocation module requires an initial biomass available for somatic growth for each plant (SGr) at the beginning of each time step: The energy budget model (Fig 1) will provide such value. Plant net water gain will be calculated in the first place using hydrology and allocation variables’ values following the ESPR equations (Cabal et al. 2020), and then transformed into a gross primary productivity based on plants’ water use efficiency. Subtracting maintenance costs of existing biomass respiration and turnover, we obtain the net primary productivity, which is the new biomass that can be allocated into reproduction (fecundity, f, is the fraction allocated into reproduction) or somatic growth (the remaining 1-f).

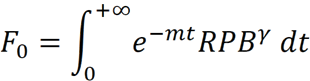

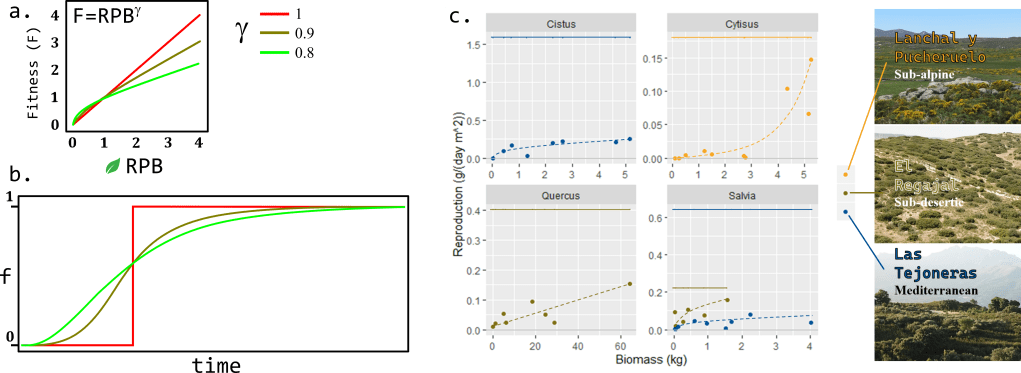

Dryland plants must face harsh environmental conditions that either reduce their growth rates and/or increase their probability of dying. Based on the theory of optimal resource allocation (Kozłowski, 1992), living organisms face reproductive time trade-offs in the course of evolution (Jönsson, 2000; Obeso 2002). On the one hand, reproducing at a given size implies marginal costs due to reduced resources available for growth, and delaying reproduction allows for a more substantial size increment that may pay back in future reproduction events. On the other hand, probabilistic survival should promote reproducing precociously to avoid dying before first reproduction. Under the premise that plants must maximize their lifetime fitness, we may expect that species have optimized their resource allocation into reproduction for the environmental conditions they are adapted to, and this allocation into reproduction must constraint plants growth and individual size at a demographic level (Iwasa & Cohen, 1989; Pugliese & Kozłowski, 1990). During my PhD, using dynamic optimal control theory (Dixit, 1990), I developed a simple energy budget model for woody plants growing in stressful conditions (unpublished). Assuming that increasing reproduction allocation had diminishing returns (power law, ) on fitness, due to negative density dependence in the propagule population (Fig 2a), plants on the model maximized their lifetime fitness returns (F0) leveraging two life history parameters, the probability of dying based on a mortality rate m, and their lifetime fitness, over time:

Model results showed that, when there is no diminishing returns (=1), plants allocated all of their biomass into somatic growth (f=0) until reaching an age at which they switched strategy and started allocating all their NPP into reproduction (f=1), which replicates the behavior of monocarpic plants. Nevertheless, when I incorporated diminishing returns (1>>0) plants showed a sigmoidal, gradual shift from f=0 to f=1 (Fig 2b). The later result fits better the life history of woody plants adapted to stress conditions as reported in the scientific literature (Wenk & Falster, 2015) and according to my own data (Fig 2c, unpublished).

For the energy budget module of RooMoHR_ I plan to apply this approximation of reproduction allocation to incorporate realistic plant growth dynamics. Plants’ allocation into reproduction will increase progressively hence limiting plant growth and maximum plant size. This biomass allocated into reproduction will feed the demography module at the next time step. The remaining part of NPP will be the biomass available for somatic growth; SGR = NPP(1-f).

- Cabal, C. et al. (2020) The Exploitative Segregation of Plant Roots. Science 370

- Kozłowski, J. (1992) Optimal allocation of resources to growth and reproduction: Implications for age and size at maturity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 7, 15–19

- Jönsson, K.I. (2000) Life history consequences of fixed costs of reproduction. Ecoscience 7, 423–427

- Obeso, J.R. (2002) The costs of reproduction in plants. New Phytol. 155, 321–348

- Iwasa, Y. and Cohen, D. (1989) Optimal Growth Schedule of a Perennial Plant. Am. Nat. 133, 480–505

- Pugliese, A. and Kozłowski, J. (1990) Optimal patterns of growth and reproduction for perennial plants with persisting or not persisting vegetative parts. Evol. Ecol. 4, 75–89

- Dixit, A.K. (1990) Optimization in Economic Theory, Oxford University Press.

- Wenk, E.H. and Falster, D.S. (2015) Quantifying and understanding reproductive allocation schedules in plants. Ecol. Evol. 5, 5521–5538